SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL

PUBLISHED OCTOBER 1, 2025

A couple of weeks ago I shared some details of the last will and testament of Mr. Richard Clarke – my wife’s great-great-grandfather. Wills looked quite a bit different in 1903 when his was drafted. There was one other provision in his will which does have some relevance today. It provided that “the four chickens that are owed to me by my son William I hereby forgive and are bequeathed to him.”

Okay, I’ll admit that most parents today aren’t lending the kids four chickens – or any manner of fowl or livestock. But parents today are, more than ever, helping the kids financially by lending – or giving – funds to help with the down payment on a home, to start a business, or simply to help make ends meet in a world that has become unaffordable for many.

Make a Letter of Wishes part of your overall estate plan

The question: What happens to these amounts when a parent passes away? And what if different children have received different amounts over time? Your will should deal with these amounts in one way or another. Today, let’s talk about how to deal with this issue by asking four questions.

1. Have you advanced funds to your children?

If you’ve already advanced funds to one or more of your kids, was your intention to make these loans, or gifts? There’s a difference – and it matters. In some cases, parents have lent funds to help with the down payment on a home and have taken back a mortgage on the property. This can protect the property in the event the child is married and later gets divorced (you could demand payment on the mortgage in that case). In other cases, the amount is a gift and won’t have to be repaid. Loans you’ve made are an asset (a receivable) that forms part of your estate – but gifted amounts are not. Is it clear to your children whether funds they’ve received are a loan or gift?

2. Have you documented any advances?

Documenting advances to kids is important – especially if you plan to equalize inheritances for your children so that each ultimately receives the same amount. When you’re gone, your executor will need to know how much was advanced to each beneficiary. How should you document advances? As a minimum, you should maintain a spreadsheet with that information, and make sure your executor knows where to find it. Even better, provide an e-mail to your lawyer, accountant, or executor with details of each advance (and copy the child receiving the funds on that e-mail). If the amount is a loan, the best documentation is a promissory note signed by you and the recipient of the funds. A separate promissory note for each loan amount makes sense.

3. Is your plan to forgive any loans made?

Whether you plan to forgive any loans after you’re gone, or not, there should be language in your will to address your intentions. If you want to forgive any loans, your will should state that you’ve lent funds to a child, or children, and that you forgive all amounts owing at your date of death, and that your executor should cancel any promissory note and deliver a copy of this to the respective children. And if your intention is to not forgive loans, your will can say that loans should be collected upon your death (you should include the details of any loan, like the amount and whether it’s secured or not). If you have a spouse, you should also mention whether the intention is to forgive or collect the loan upon your death, or your spouse’s.

4. Is your plan to equalize inheritances among beneficiaries?

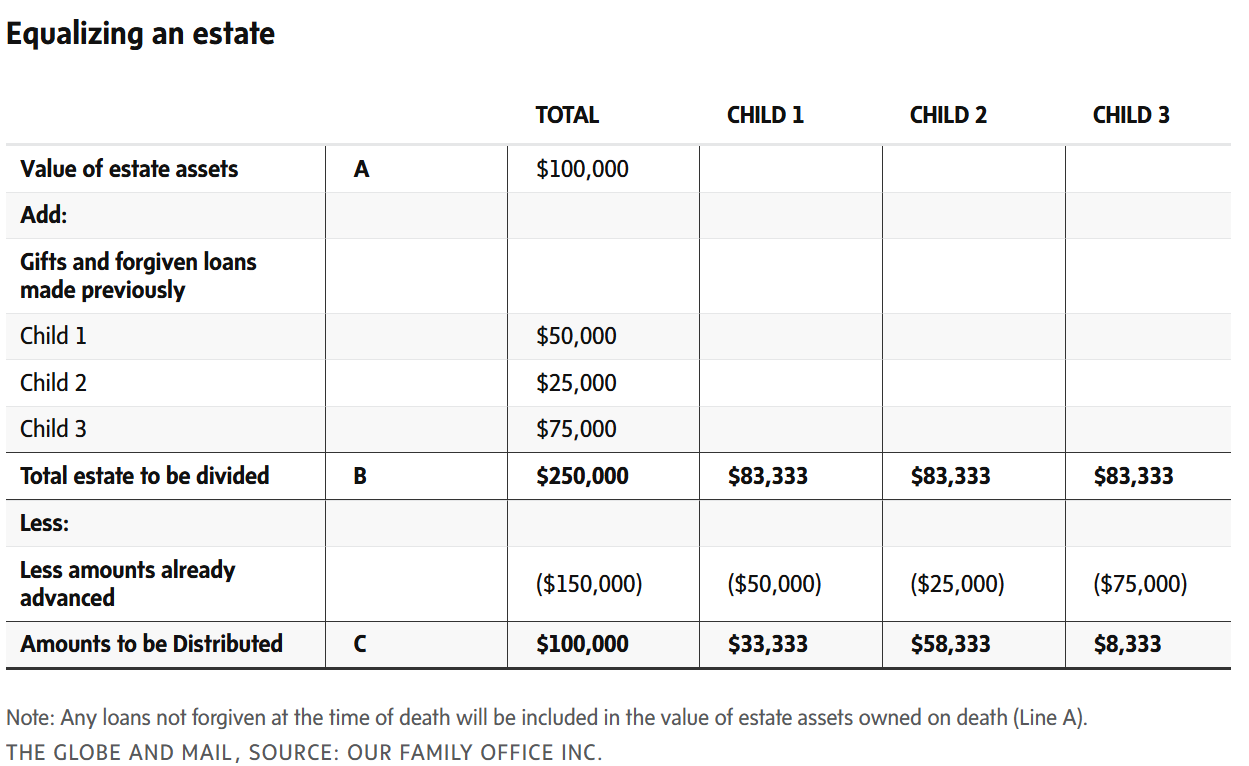

Finally, if the advances you make are considered gifts, or forgiven loans, is it your intention to treat all beneficiaries equally when your estate is distributed? If so, your will should include a “hotchpot” provision. In this case, your executor will add the value of all these gifts and forgiven loans to the total value of the estate. This total will be divided equally between your beneficiaries, then the funds advanced previously will be deducted from each heir’s share (see the accompanying table). The result? Children who received more during your lifetime will receive less after your death, and everyone will ultimately receive an equal share.

Tim Cestnick, FCPA, FCA, CPA(IL), CFP, TEP, is an author, and co-founder and CEO of Our Family Office Inc. He can be reached at tim@ourfamilyoffice.ca

Download a copy of this article in pdf here.

North American Wealth Award Nominations 2020:

Finalist in 3 Categories

What do I want to share with my heirs about my values and life experiences while I still can?

What do other successful families do about educating future generations?

What would happen to my family and business if I were suddenly gone tomorrow?

Is it possible that there might be other tax ideas we haven’t considered yet?

Who will make the important decisions and coordinate things after I’m gone?

Do I wonder sometimes if our planning done in the past is still relevant?

Are my investments properly compensating me for the risk I’m taking?

Which of my investments or accounts are no longer serving their intended purpose?

What do I expect market returns to look like in the next five years?

What is my Strategic Asset Allocation?